Types of Government Contracts and the Basics of How They Work

Learn the fundamentals and types of government contracts, including the history, obligations, and risks associated with each category.

Updated November 2023

A Brief History of Government Contracts

There are generally three types of government contracts:

Each type has unique requirements, risks, and demands from a contractor.

In addition, they may be structured in two different forms: completion form or level of effort (term form).

The completion forms obligate the contractor to deliver an item or complete a task in order to be paid. The level of effort forms obligate the contractor only to provide a specified level of effort, stated in hours of certain labor categories, in pursuit of an objective set forth in the contract statement of work (SOW). Achievement of the objective (completion) is not required, only the contractor’s good faith best efforts in pursuit of the objective.

Understanding the contract types and forms is essential to providing a competitive bid and executing on a contract while mitigating the inevitable risks.

In this blog, you'll learn:

- The three most common types of government contracts

- When they are used

- What you need to know regarding the risks associated with each one

Types of Government Contracts

1. Fixed Price Contracts

Let’s look first at the fixed price contract. Overall, the government obligates more money on fixed price contracts than any other — about two thirds of all obligations in recent years.

Fixed price contracts are the preferred contract type by law when the requirements or specifications are known and can be described and measured precisely. In general, they are just what you would expect; specific performance for a set price.

The Completion Form (FFP)

In the case of completion form contracts, often referred to as firm fixed price or FFP, contractors provide a bid or proposal to complete a project for a fixed price.

The project could be to deliver an item or multiple items, or to perform a specific service. The key characteristic of the fixed price completion form contract is that all risks associated with cost or performance are born by the contractor. If all requirements can be precisely described, cost of performance can be reasonably predicted and the risk may be mitigated, but it is still considerable. In the end, if the contractor does not complete the contract, the government does not pay.

The government has little or no risk in a fixed price contract.

And the fixed price does not change unless there is a negotiated modification to the contract to change the scope or agreed upon provisions that would allow for adjustment of the price. Fixed price completion form contracts are mandatory for commercial items and very common even for “build to print” items if the feasibility of building the items is relatively certain.

Fixed price completion form contracts for services are somewhat rare. This is primarily because of the difficulty in writing a performance statement of work that precisely describes when the services can be considered complete.

The Level of Effort Form (FP-LOE)

The level of effort form is primarily used for services or, occasionally, for research and development when the requirements or specifications cannot be precisely described.

Normally, a cost-reimbursable type of contract would be appropriate in that situation. But if the contractor’s accounting system is not adequate for collection and reporting of costs on a cost type contract, FAR prescribes use of a fixed price level of effort contract instead. The only thing required to support an FP-LOE contract is a timekeeping system that can substantiate the hours worked by labor category and project or task.

The contractor’s obligation under this form of the fixed price contract is to deliver exactly the hours specified in the level of effort clause of the contract and to provide its “best efforts in pursuit of the objective set forth in the statement of work.”

In fact, level of effort contract forms are sometimes referred to as “best efforts” contracts. If the level of effort requirements are not met in full, the contract requirements are not fulfilled, and the government may not pay the fixed price. Contracting officers have considerable latitude to accept slightly less than the exact level of effort, particularly if the objective of the SOW has been accomplished, but they are under no obligation to do so. If more hours are provided than are called for in the level of effort, the government will not usually pay any extra.

Normally the government pays only upon delivery of the full level of effort. But this can impose a significant financing burden on the contractor if the contract last more than a few months.

Fixed level of effort contracts will sometimes contain a special provision or clause that provides for periodic billing (usually monthly) much like a time and materials contract.

2. Time and Materials Contracts

Like the fixed price level of effort contract, a time and materials (T&M) contract contains a special provision or clause setting forth the hours by labor category to be delivered under the contract. Also like the FP-LOE, T&M contracts do not obligate the contract to complete the work.

All T&M contracts are, effectively, level of effort or “best efforts” contracts. Most T&M contracts are also “term form” contracts in that they have a fixed period of performance (POP). The government ordinarily will not pay for hours worked before the POP starts or after it ends.

Instead of a fixed price for the contract, T&M contracts contain a schedule of hourly rates by labor category for the labor along with a “not to exceed” cost for materials, travel or other non-labor costs. That "not to exceed" will typically also include the application of the contractor’s general and administrative (G&A) rate on the non-labor costs. For administrative convenience, the contract may provide instead for a fixed markup on those costs rather than a re-determinable indirect cost rate.

If the objective of a contract is well defined, but the general timeframe is uncertain or unknown, a T&M contract may be appropriate. T&M contracts always have an overall not to exceed price that cannot be exceeded without a contract modification. The government’s sole obligation under a T&M contract here is to pay for the hours delivered and accepted pursuant to the statement of work. The contractor’s obligation is to pursue the objectives of the statement of work in good faith through application of the categories of labor in the contact.

One more thing: The contractor is obligated to stop working when the money runs out.

If a contractor continues to perform beyond the POP or in excess of the obligated funds, there is no expectation of payment.

The contractor has no performance risk under a T&M contract, but is exposed to cost risk associated with the fixed hourly rates in the contract. If a T&M contract extends for multiple years, inflation can adversely affect profitability in the out year if those rates were not appropriately priced or the rate of inflation exceeds the assumptions used in the pricing.

There is a variation of the T&M contract type called a labor hour contract. It is nothing more than a T&M contract with no non-labor costs allowed (just “T,” no “M”).

3. Cost-Reimbursable Contracts

This type of contract reimburses the contactor for the actual costs incurred in performance of a project up to the amount obligated on the contact as specified in the Limitation of Costs clause or the Limitation of Funds clause. Direct costs are reimbursed as they are incurred at actual amounts. Indirect costs are reimbursed at provisional rates subject to later audit, redetermination, and adjustment.

All contracts require estimation of the costs of performance.

But sometimes there is so much uncertainty associated with the statement of work that no contractor would accept the contract for a fixed price or that the risk to the contractor would be unconscionable. Cost-reimbursable contract are used in these circumstances.

In extreme cases, it may not even be certain that the task(s) in the statement of work are even possible.

This is a perfect example of when a cost-reimbursable contract would be appropriate. In more normal scenarios, it might be reasonably certain that the task is feasible, but something about the work makes it very difficult to predict the cost of performance. When costs cannot be predicted with any degree of certainty, a cost type contract might be appropriate.

Cost-reimbursable contracts may also be of either a completion form or a term form, level of effort. Both are subject to the Limitations clauses and both require the contractor to stop work when the money runs out.

The primary difference is the contractor’s obligation.

Cost-Reimbursable Contracts: The Completion Form

With the completion form contract, the contractor is obligated only to diligently pursue the objectives of the statement of work subject to the limitations of the funding.

If the money runs out and the work is not complete, additional funds may be provided (referred to as an “overrun” or, more commonly, as a cost growth). The government is under no obligation to fund the cost growth and the contractor is under no obligation to continue performance. If funding is provided for the overrun, no additional fee is included – only funding for the additional costs.

If the overrun is large, it can significantly dilute the contractor’s profitability on the contract.

Cost-Reimbursable Contracts: The Term Form, Level of Effort

With the term form of the contract, there will be a special provision or clause setting forth the hours by labor category to be delivered under the contract.

There will also be a period or performance (POP) or term. Unlike the T&M contract, there is no fixed rate associated with each labor category. Instead, all costs of performance are reimbursed as in the completion form.

If the contractor does not deliver the full level of effort in accordance with contract clause by the end of the term, such contracts typically require a pro rata (downward) adjustment of the fee.

While the contracting officer has considerable latitude, the government is not obligated to reimburse labor or non-labor costs incurred after the end of the POP. If the term ends and there are hours unexpended and the government has a continuing requirement for the services, no-cost extensions of the term of the contract are common.

If the hours or the money runs out with time left in the term, the government may modify the contact to add additional money, hours, or both, but they are under no obligation to do so.

The Fee Structures of Cost-Reimbursable Contracts

1. The fixed fee.

The most common fee structure for cost-reimbursable contracts is a fixed fee.

Cost type contracts with a fixed fee, whether completion form or level of effort, are referred to as Cost Plus a Fixed Fee or CPFF contracts. The fee is fixed and does not vary based of costs.

It may, however, be adjusted on level of effort contracts if the full hours are not delivered.

2. The award fee.

Another common fee structure for services contracts is an award fee.

With these contracts, the fee is separated into a base fee and an award fee. Such contracts are referred to as Cost Plus an Award Fee or CPAF contracts. The base fee can be, and often is, zero with all of the fee available only as an award. The base portion of the fee, if any, is paid in the normal course of invoicing, but the award fee is paid only at the end of each evaluation period based on performance.

The total award fee amount available for each period is set out in the contract.

The contractor’s performance is measured at the end of each period, usually three or four times a year, based on metrics and criteria in the contract, and a report card is issued by the government customer. The fee “awarded” for the period is based on the percentage attainment of the criteria or goals in the contract.

Award fee contracts are fairly common in research and development (R&D) but not particularly common for services. They are very expensive and time consuming to administer and so are not often used for small, or even mid-sized, contracts.

3. The incentive fee.

Another fee structure designed for R&D work is the incentive fee.

The fee on these contracts can also be separated into a base fee and an incentive fee, but more often than not the base fee is zero. Such contracts are referred to as Cost Plus an Incentive Fee or CPIF contracts.

The incentive portion of the fee is associate with one or more performance characteristics of the item under development and a separate cost incentive. FAR does not permit use of an incentive contract with only performance incentives. There must always be a cost incentive. With the fee already dependent on two or more incentive calculations, one performance and one cost, it is easy to see why the base fee is often zero.

Further division of the fee beyond the multiple separate incentives would likely make each individual incentive too small to be effective.

A classic example of a CPIF contract is development of a man-portable rocket like the Javelin. In addition to a cost incentive to reward the contractor for cost control, there might be a fee component to incentivize the contractor to design the system to be as light as possible while still meeting the performance specifications (range, accuracy, etc.).

CPIF contracts are even more expensive and time consuming to administer than CPAF, which is why they're often used for small, or even mid-sized, contracts and almost never for anything other than R&D.

4. Cost contracts and cost sharing.

Occasionally the government will take the position that the contractor stands to benefit substantially from commercial application of the technology under development.

In such cases, the government may seek to award a cost-reimbursable contact with no fee at all or even a contract where the reimbursement is partial. The former is referred to as a Cost No Fee contract and the latter as a Cost Sharing contract.

Both are very uncommon and almost never seen outside of R&D.

Hybrid Variations

There is always potential for variation.

Some contracts have a mixture of fixed price, T&M or cost-reimbursable provisions for different parts of the project. These hybrid contracts can be quite lucrative for those who understand the ins and outs of the different types. Hybrid contracts are experiencing an increase in usage in recent years. The hybrids evolved from the strong government preference for fixed price contracts arising out of the Competition in Contracting Act.

A hybrid example might be fixed price contract for items with T&M provisions for support or installation of the items after acceptance.

What's the Most Common Type of Government Contract?

So, how much money does the government spend on contracts, and how much is obligated against each type?

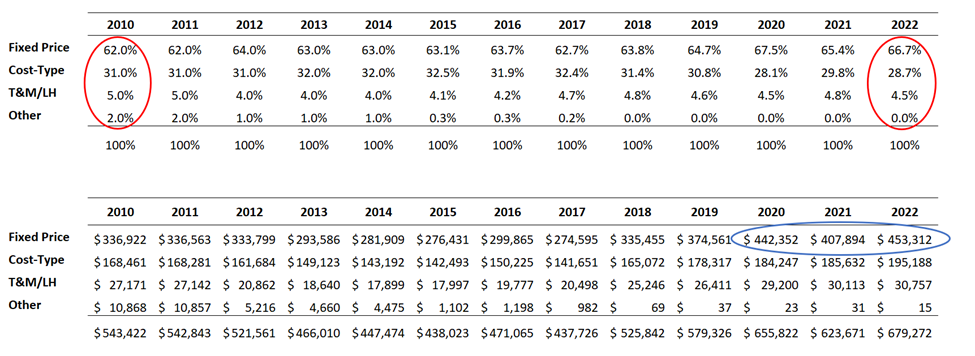

The chart below shows the contract mix both in dollars and as a percent of the total for the year.

Note that there is a lot of money obligated on fixed price contracts. This is not because fixed price is inherently better or worse, but because very large production and almost all construction contracts are always fixed price. While it is a lot of money, it represents a relatively small number of contracts.

You will notice that cost-type contracts have been between 28.7% and 32% of the total for 13 years. This stability is a result of the principle that what the government buys determines the level of risk and the level of risk determines the type of contract.

All the pounding on the podium that politicians do and all the preferences for the types of government contracts has had little impact for 20 years. The number of dollars spent on cost type and T&M contracts is still roughly the same proportion—approximately a third of all procurement spending—simply because about a third of everything the government buys can’t reasonably be acquired for a fixed price.

This is because some important factor is unknown — either the specifications, when it’s needed, where it’s needed, what is needed, or something similar, that makes the risk inordinately high.

Contracting Risks

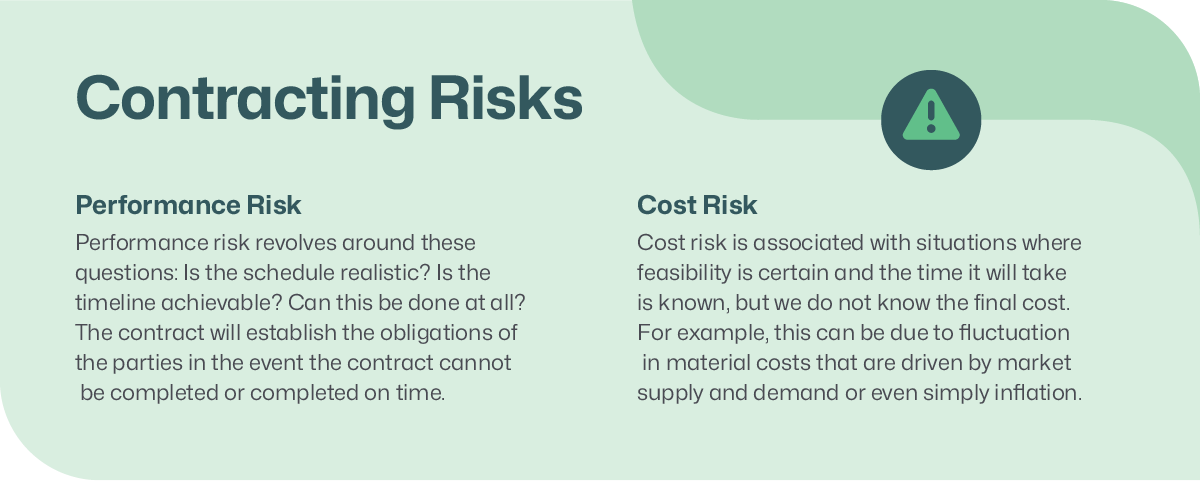

Risk is inherent in all contracts and varies depending on which side of the contract you sit. It is a very important aspect of contracting, and it comes in two forms: performance risk and cost risk.

- Performance risk revolves around these questions: Is the schedule realistic? Is the timeline achievable? Can this be done at all? The contract will establish the obligations of the parties in the event the contract cannot be completed or completed on time.

- Cost risk is associated with situations where feasibility is certain and the time it will take is known, but we do not know the final cost. For example, this can be due to fluctuation in material costs that are driven by market supply and demand or even simply inflation.

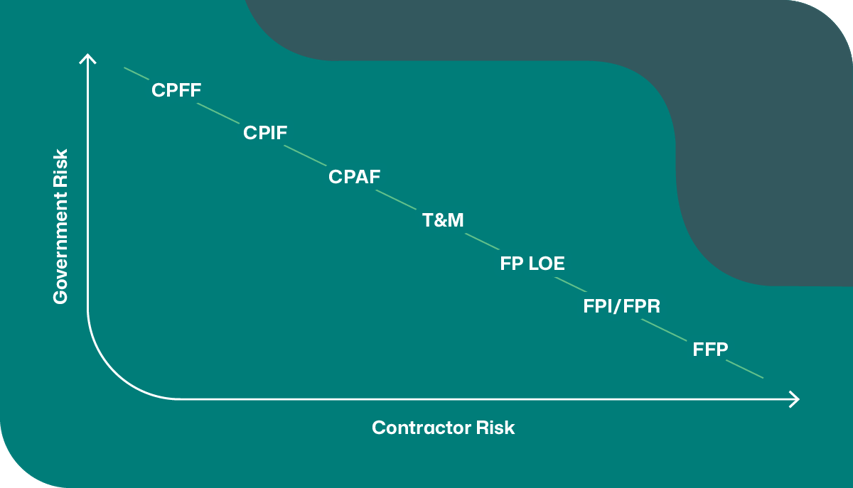

Risk is a spectrum across the types of government contracts and can vary with the specific statement of work and the nature of the costs.

A contract of a type that is usually very risky for a contractor could be attractive if the contractor is very comfortable with the work and the costs are well known. On the other hand, a contract of a type that is usually much less risky could turn out to be fraught with risk if the skills of the workforce turn out to be poorly matched to the work or the costs are subject to unpredictable market fluctuations.

In general, though, the diagram below shows the relationships between the different contract types and forms based strictly on differences in risk.

Party Obligations for Each Type of Government Contract

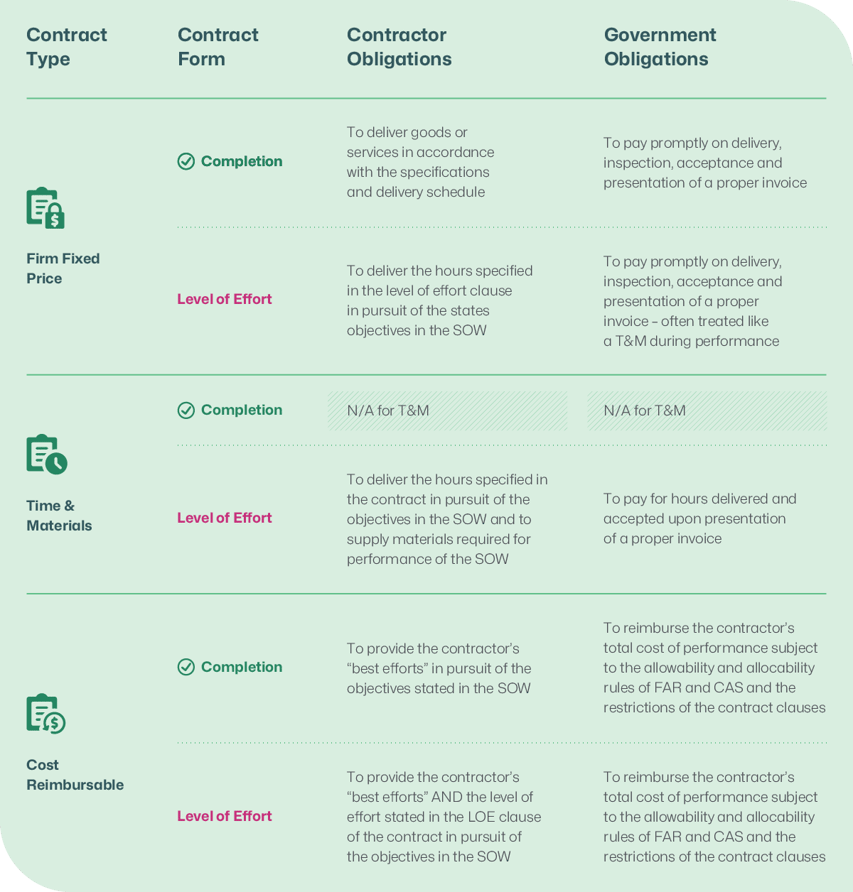

Aside from risk, the obligations of the parties is the primary differentiator between the types and forms of contracts.

Any contractor performing services or delivering goods to the federal government, needs to understand its obligations under the contract and the government's obligations to the contractor. The summary chart below may help differentiate between the types and forms of contracts.

How Is the Type of Government Contract Determined?

Here is where a government contract really differs from a commercial negotiation.

In the commercial world, the contract type is a matter of agreement between the parties. The buyer and the seller agree on what kind of contracting arrangement will be used. But in the government world, that’s all determined before the solicitation is ever issued.

There is not a choice of contract type.

Competition, price, predictability of cost and pricing, complexity and feasibility of the work, and the timing of the requirement are all factors that play into the upfront contract type selected for each procurement by the contracting officer. Government contractors rarely have much choice about the types of contracts on which they submit bids or proposals.

But they certainly need to understand the impact that contract types have on the financial health and well-being of the company.